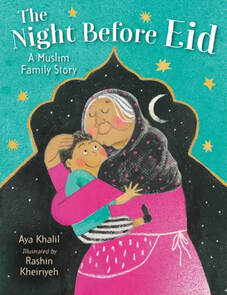

In the fall of 2021, I learned that my debut picture book, The Arabic Quilt was on a banned book list at Central York District. It was taken off of shelves and children were not allowed to read them. The book that took years to write and find a publisher. The book I was receiving dozens of emails and messages about how kids’ eyes lit up when they saw an Arab or Muslim character on the cover. The book that I had stayed hours at the library to research. The book I devoted a lot of time to learning about the publishing industry for. The book I met up with critique partners for, and stayed up late to revise and edit, long after I had put my young kids to bed. Some people say I’m lucky that the book is now a banned book because of the attention it would get. But I disagree; there are only a few picture books by Arab Muslim American authors. For a period of time, students weren’t able to check out The Arabic Quilt from their libraries, and this picture book could have been the only book with a positive portrayal of an Arab Muslim. The censorship and ban were upsetting and another hurdle as an author of color. It’s a privilege not to have to worry about whether or not your book will be banned because of who the characters of the book are and the theme of the book. The book ban reminded me why I was so adamant, and so persistent about publishing The Arabic Quilt in the first place. Navigating the world as a Muslim and an Arab is challenging in its own right but these challenges are multiplied further in the world of publishing, something I believe many BIPOC authors can relate to. The microaggressions I, as well as many other BIPOCs face on a daily basis and within the publishing industry itself, is partly because we never got to tell our side of the story or our stories weren’t heard or we were rarely ever the heroes of stories. In fact, we were always the villains, or the victims. Growing up in the U.S. I never saw characters who looked like me, a Muslim, Arab American in TV, movies, or in books with positive portrayal. I am 35 years old and the first time I saw a character with my name, Aya, in mainstream media in the U.S. was when I was 34. It was a powerful moment and I almost couldn’t believe it. I didn’t want BIPOC children to have to wait as long as I did to feel seen and to feel proud of the way they were being portrayed. In 2005 after I graduated high school I told my parents I would not go into medicine, law, or engineering like most of my friends around me from my Islamic High School. I would go on to study communication and English literature and use the power of my words to control the narrative. To tell our stories. To tell my story. Years passed with this dream in mind. I worked as a freelance journalist for a decade and earned my master’s degree in Education but it was only when I had my own children and became a teacher that I started turning this dream of telling our stories into a reality I was surprised at how the bookshelves in the classrooms I was working in didn’t reflect the demographics of the students I was teaching. Most of the books had white children on the cover, but the majority of the students were BIPOC. I came across a few self-published picture books by Muslim authors that had Muslim characters. There were only a few out there but it was still hard to find them at libraries or to come across them at bookstores. A few picture books were getting published by traditional publishers around the same time and it was mind blowing to me that Muslim kids could casually find these books at bookstores and the library. Books with characters that looked like them: unapologetic Muslims living their everyday life and being the heroes of their stories. After seeing a call out to Muslim authors from a literary agent around the same time former President Trump announced a Muslim ban in 2017, I decided it was time for me to tell my stories through children’s books. I went through the hurdle of querying literary agents. After struggling for some time with rejections I reached out to other authors who gave me feedback on my manuscript and I joined a local picture book critique group and took book-writing classes. When I was offered representation by a wonderful literary agent, Brent Taylor, who somehow believed in my picture book manuscript, I thought all the hard work was finally over. Boy was I wrong. Months went on and we were getting rejection after rejection. Some rejections were more courteous and even came with feedback. Other rejections, however, made it clear that some publishers weren’t willing to risk publishing a story about a Muslim, immigrant child, and by an unknown debut author no less. I told myself it was okay to set this to the side and forget about it. Maybe I should just stick to non-fiction; to journalism and continue to blog and pitch pieces to magazines and newspapers. Then one hot summer day in 2018 when I was walking my kids to Arabic school, I opened my email and was shocked to see that a small independent publisher was interested in The Arabic Quilt. I was ecstatic, as they had published one of my favorite picture books, Laila’s Lunchbox a few years earlier and it was what inspired me to write a picture book and traditionally publish it. I couldn’t believe it at first but I will never forget how at that moment, I thought, I think this is it. My words are going to be out there for kids to read. In 2020, in February, right before the pandemic hit the U.S., my debut was published, and it was beautifully illustrated by Anait Semirdhzyan. My publisher emailed me a few days later saying it was flying off the shelves and it was getting sold out quickly in a lot of places. This was surprising to me, as I wondered how many people would be interested in reading a picture book about an immigrant Muslim girl named Kanzi. Moreover, I was still thinking (and upset to be honest) about the mixed review from a popular trade review magazine that said the dialogue in the book was “stilted” and the message was “outdated.” I felt this was unfair, as the book was based on my real experiences as an immigrant and Egyptian child, but I was also reminded that these reviews were subjective. After a few more weeks, we learned our book earned a starred review from the School Library Journal and later had won numerous prestigious awards. The best part though, was getting messages from Muslim and/or Arab parents saying their children’s eyes lit up when they found the book at the library or bookstore or when their teachers read the book to them in their classroom. They felt seen. How I wished I had this book, and other books with positive Muslim portrayal growing up. It is their positive feedback that encouraged me to continue writing and as of 2022, I have another book that was published this fall, Our World: Egypt, a board book filled with love and joy between an Egyptian dad and his daughter, something rarely portrayed in the media. In 2023, I have three books coming out: The Night Before Eid, illustrated by Rashin Kheiriyeh out on March 7th and The Great Banned Books Bake Sale, illustrated by Anait, out on August 1st, which is loosely based on the true story of when The Arabic Quilt was banned. Fortunately, the ban against my book was also lifted shortly after thanks to student protests at the district and an outcry from around the country. Around the same time, I also learned that two districts across the country had purchased tens of thousands of copies of The Arabic Quilt for their curriculum. Despite these achievements, there’s still work to be done. Arab authored books are still underrepresented. In 2019, 1.2 percent of books had a Muslim diversity subject, although the accuracy and quality weren’t evaluated. I am often put on book lists during Asian American Heritage Month or not put on book lists for Arab American Heritage Month while Asian authors are put on there. In 2023, I hope more people support books by Arab authors. I hope editors buy more of these books and agents take on more Arab. However, despite the regular challenges of any author who is querying agents and going on submission to editors, BIPOC authors have an additional struggle during this arduous process. When editors or agents tell us they already have “a Muslim author” on their list or “an Arab author” client, but their lists are filled with white authors and animal characters. Moreover, another heartbreaking type of rejection BIPOC creatives get is being told that publishers already have enough of a certain type of story on their list and it’s already oversaturated, although we never had the chance to tell that story with our voice. It’s also worth mentioning that going into this industry, you will be doing a lot of educating. Educating illustrators, editors, copyeditors about things that must stay or be removed in the story or illustrations. It can get exhausting at times, but it’s important information for our stories to stay authentic and true as possible and educating is a key part in that. At the Muslim Storytellers Fellow Highlights Retreat, I found myself sitting alongside talented Muslim authors, writers and illustrators. We shared our struggles about navigating the publishing industry, but reminded one another about the importance of storytelling. Our readers keep us going. Our children keep us going. Our teachers and librarians keep us going. Our families and friends keep us going. Rejections are part of this journey, and we will continue to face microaggressions and struggles along the way, but the love and passion we have for publishing our stories keeps us motivated. Being a marginalized author in this industry is no easy feat, but it is worth it when you know you’re making a difference in children’s lives and normalize unapologetic Muslim stories. It’s time we continue to reclaim our narrative and continue to be the heroes of our stories because our stories have been here for a long time and they’re here to stay. I hope readers will continue to see themselves in my books and I hope they love The Night Before Eid, which can be purchased here on March 7th. Aya Khalil, M.Ed, is the award-winning author of The Arabic Quilt: An Immigrant Story, which is an NCTE’s Charlotte Huck Award Recommended Book and the winner of the Arab American Book Award, among other honors. She's also the author of Our World: Egypt and The Night Before Eid. Aya holds a master’s degree in education and her articles have been in The Huffington Post and We Need Diverse Books, among other publications. She immigrated from Egypt to the United States when she was one and lives with her husband and children in Northwest Ohio. Her website is www.ayakhalil.com Comments are closed.

|

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed